Yvonne Shields O’Connor, Irish Lights and Lar Joye, Dublin Port, tell the story of Dublin as part of a series of articles following sailor Jonathon Winter on his voyage around Ireland and the UK.

Like many capitals, Dublin has grown over the last 60 years attracting people, business and government agencies. It is an international city with a large financial district based in the former docklands area, often referred to as ‘Silicon Docks’ with almost two million people living in the metropolitan area. At the same time Dublin Port has expanded and is now the largest port in Ireland.

Dublin was not always the country’s dominant city. In the 17th century Dublin bay presented major dangers for shipping and trade with Britain and Europe. In 1674 its natural state was described as “wild, open and exposed to every wind, no place of shelter or security to ships”. With strong tides, sandbanks and little shelter, ships frequently had to seek protection at two small seaside villages, Clontarf to the north or at Ringsend on the south of the city. In certain wind conditions ships could not reach the city for several weeks at a time. Shipwrecks were common, and it is estimated that at least fifteen hundred shipwrecks took place in the approach to Dublin port. In addition the Liffey River silted up, denying ships access to city, while many dumped excess ballast – needed when they were not full of cargo – into the river, causing blockages. As well as being dangerous to get to Dublin, too often on arrival it was impossible to enter.

These were serious problems for an aspiring port. They were unlikely to be solved while port affairs were contested between Dublin Corporation and the Lord High Admiral in London, the then Prince Consort George. However after offering to pay the Prince annually 100 yards of Irish sailcloth an Act was passed entitled ‘An Act cleansing the Port, Harbour and river of Dublin for erecting a Ballast Office in the said City’. The resulting Ballast Committee set to work and in 1716 began to build the South Bank and – when that proved ineffective – the South Bull Wall (bull is another word for strand). Over several decades the wall worked its way out to the Poolbeg Lighthouse and was finally completed in 1792. At the time it was the longest sea wall in the world, measuring 5km.

Many Dublin merchants were dissatisfied at the slow progress of building the wall and in 1786 control of the Port was transferred from Dublin Corporation to a new authority, the Corporation for Preserving & Improving the Port Of Dublin, which was controlled by merchants and property owners and also had responsibility for lighthouses in Dublin. Later in 1801 it was also given responsibility for maintaining lifeboats in Dublin bay, and in 1810 under the Lighthouses (Ireland) Act, its lighthouse remit was extended to the whole island.

Even with the wall in place, almost a century later silting remained a problem. Greater ingenuity was required. In 1800 a major survey of Dublin bay by Captain William Bligh (of HMS Bounty fame), recommended that a North Bull Wall be constructed to prevent sand building up in the mouth of the harbour. It was a controversial and clever plan. Bligh forecast that this new wall would hold back the water at high tide, diverting it to create a natural scouring action that would deepen the river channel where needed. It worked, and when the wall was completed in 1824 sand gradually accumulated along its side until an island emerged called Bull Island. Two hundred years later this is now a nature reserve, beach and part of the Dublin bay UNESCO designated biosphere. Both walls are still providing the function of keeping the modern Port open.

Throughout the 19th Century the Port expanded eastwards from the City, its growth fuelled by the arrival of the railway in 1840s which made Dublin and the Port the centre of a 4,200km network of railway track. This allowed travellers to leave the West of Ireland and be in London by the end of the day. A new Custom House was built on reclaimed land, but the eastward shift for the city was opposed by many citizens who had their business in the older medieval city based around Dublin Castle.

From the 1860s construction work began on deep-water quay walls. More clever engineering was needed. Port Engineer Bindon Blood Stoney designed a 90 ton Diving Bell, crane and barge to speed up the building of the new quays. The Bell was open at the bottom and allowed six workmen to descend down a funnel through an air-lock to work on the river bed. Their task was to level the river bed to make way for large prefabricated concrete blocks, each weighing up to 350 tons. In 2014 Dublin Port Company decided to display the Diving Bell, which had been saved, by raising it off the ground and building a small museum underneath. “Now suddenly it’s Dublin newest museum – a miniature one, to be sure, but packing more fascination per square metre than most others” (Frank McNally, Irish Times). The museum has 110,000 visitors a year.

In 1867 came another name change, when the Dublin Port Act separated port activities into the newly constituted Dublin Port and Docks Board and the Lighthouse Department became the Commissioners of Irish Lights. A bespoke headquarters office was built for the Port, with the Commissioners of Irish Lights next door demonstrating the close relationship that existed between the two organisations. What made the building famous and distinctive was the ‘Ballast Office Clock’ mounted over the front door. In 1870 the clock was connected by telegraph wire to Greenwich Observatory making this the most accurate public clock in Dublin at the time. It became established as a popular rendezvous point for people – ‘Meet you under the Ballast Office Clock’ was a well-known refrain in Dublin.

The Irish Free State was created on 6th December 1922 with the last British Army soldier leaving on Sunday 17th December from Dublin Port. The consequences for the Port were substantial as imports from England were no longer exempt from customs regulations. Bonded transit sheds, warehousing and customs facilities had to be built. During World War II Ireland remained neutral, a period that is called ‘The Emergency’. Naturally fewer ships visited the Port but expansion continued. The 1950s brought the first roll-on, roll-off services, and container traffic increasingly dominated Port business from the 1960s.

Since 1997 the day to day running of Dublin Port has been managed by the Dublin Port Company (DPC) which traces its roots back 300 years. DPC is a self-financing private limited company wholly-owned by the State. Previous tensions over the make-up of the Board, labour strikes and the role of the government have been resolved as the Port is now a landlord port with stevedoring and ferrying companies responsible for physically importing and exporting Irish trade.

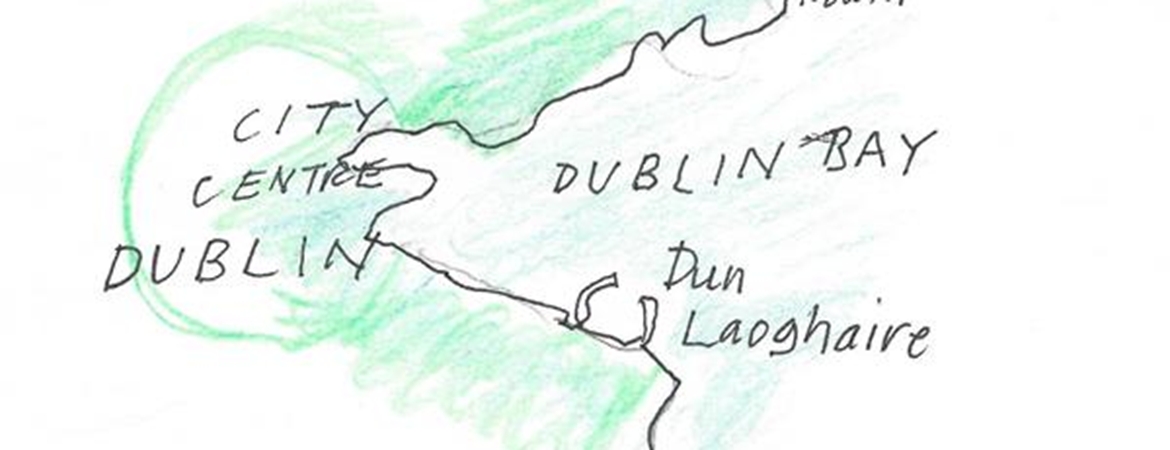

Is this the end of the story? As Ireland’s biggest port, Dublin continues to expand and the Dangerous Bay has been tamed through a combination of heavy engineering and aids to navigation. Irish Lights, while best known for its lighthouses, also operates a whole range of modern visual and electronic aids to navigation and maritime support services around the entire island of Ireland – protecting lives, property, trade and the environment around the coast. Since 1998, located in a new building across the bay in Dun Laoghaire, Irish Lights continues to collaborate with the Port on important safety, navigation and heritage projects.

The port city of Dublin now looks to the future. Its ambition is set out in the DPC Masterplan (2012-2040) which aims to improve the capacity of the Port and reintegrate with Dublin City through its Port Perspectives Engagement Programme, protecting the nature reserves that surround it and reimagining the 300 year old Port Archive, Heritage infrastructure and buildings. This has supported a variety of artists, composers, actors and performers in the last four years including a very successful collaboration with the National Theatre in producing ‘In our veins’ by Lee Coffey and ‘Last orders at the dockside’ by Dermot Bolger. This embracing of theatre will continue in September 2020 when awarding winning theatre companies Anu Productions and Landmark Productions plan to stage a theatre show over 6 weeks to 8,000 people in the active port, based on its history.

Although affected by Brexit (and now the Coronavirus pandemic) the port city of Dublin, whose once dangerous bay was tamed through a story of ingenuity and politics, is now the economic jewel in Irelands trading crown.